In 1667, Danish naturalist Nicolaus Steno made a discovery that forever changed the way we viewed the oceans forever. The fossils were thought to have been the petrified tongues of dragons or snakes, but what Nicolaus realised was the truth was equally, if not far more terrifying. These strange objects were actually the fossilized teeth of the largest shark to have roamed the oceans, the megalodon.

As with other sharks, the megalodon’s skeletal structure was mainly cartilage. Megalodon shark remains are very rare and at best, poorly preserved, the teeth being the only reliable base on which to form a taxonomic lineage. It is worth noting, as more and more fossilised vertebrae are discovered, the more our knowledge grows.

The megalodon teeth, being very similar in appearance to the teeth of the great white, led Swedish naturalist Louis Aggazis in the 1830s to assign megalodon to the Carcharodon genus (Carcharodon megladon) of which the great white is the only example still in existence (Carcharodon carcharias).

The similarities in the teeth led many to speculate that megalodon was an early predecessor of the Great White, a popular myth to this day, but fossil records show the two species occupied the oceans at the same time. Megalodon fossils have been dated from 23 million years to only 2.6 million years ago. Great white fossils have been dated up to 16 million years ago, which means the two are close relatives, but not of the same species.

The exact taxonomy of megalodon is often disputed, putting the similarities to great white under considerable doubt, but transitional fossils of an earlier species, including a fully intact jaw, show they most likely had a common ancestor in Carcharodon hubelli, placing them both in the category of lamniform shark along with other species such as the mako.

So what can be surmised from the knowledge we have? Possibly how big the shark was?

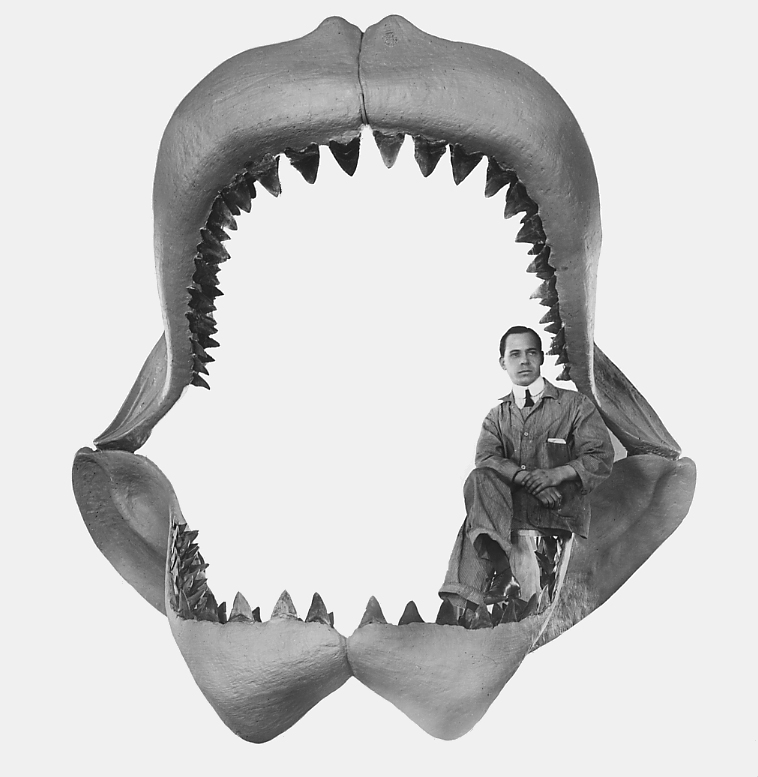

The first attempt to reconstruct a jaw of megalodon was in 1909 by Bashford Dean who estimated the shark was around 30 metres (98 ft) long. Other estimates have ranged from 20 to 26 metres (67 to 85ft). Although progress in methods later on showed this to be purely speculative, the public loves to cling onto the most extreme estimations.

In 2002 shark researcher Clifford Jeremiah set to work using a method that was found to be more reliable. Jeremiah estimated the relationship between tooth size and body length on large sharks, including its closest living relative the great white. The method consists of calculating the relationship between the root width of the upper anterior tooth and total body length. For every centimetre of root width, you have 1.4 metres (5 ft) of body length. Clifford used the largest tooth at his disposal, an upper anterior tooth with a huge root width of 12 centimeters (5 in). He then theorised it belonged to a shark of 16.5 metres (54 ft) long.

Other popular methods, such as relationship between tooth height and body length also had estimates at just over 15 metres (50 ft) in length. Applying this formula to the majority of teeth found, calculations put the average southern hemisphere megalodon sharks to be around 12 metres (39 ft) long, and those found in the northern hemisphere to be an estimated 9 metres (31 ft) long.

Such a big fish surely would have had an appetite to match. Thankfully, fossil records from other sea creatures help us shed more light on its diet.

Megalodon sharks could pretty much eat whatever it wanted. Bite marks on fossils matching megalodon teeth have been found on the bones of seals, turtles, on bowhead and sperm whales and other extinct species of whale. Megalodon teeth are often found in direct relation to the fossilized remains of chewed whale remains.

Amazingly, it is rare to see Great White shark fossils and megalodon fossils from similar time frames in the same area. This suggests Great Whites avoided megalodon sharks as they may have had cannibalistic instincts.

Megalodon teeth can still be found today. In October 2016, a Virginia couple found a large megalodon tooth that had been uncovered after hurricane Matthew.